Time Paradoxes

in 19th-Century Swedish Science Fiction

by Bertil Falk

Lecture delivered by Bertil Falk to the Tycho Brahe Society at the Town Library of Lund on Thursday, October 28, 2010.

Time is something that always has fascinated us. In the Indian epic Mahabharata, written about 2,700 years ago, a King Revaita went to the heavens to meet Brahma, the Creator. When he returns to the earth, everything had changed: the buildings, the way people dressed, the weather. He had only been away for a short time, but hundreds of years had gone by on Earth. Evidently, he had travelled at a speed near the speed of light and unintentionally triggered an Einsteinian time dilation.

I am currently working on a project with the working title Faktasin: Svensk science fictions litteraturhistoria sedan 1600-talet (The Factasy: the History of Swedish Science Fiction since the 17th Century). In the course of my work I have found two — actually three — 19th-century texts containing, not time dilations, but time paradoxes.

The first text is from 1846. I found it mentioned in passing in the doctoral dissertation “Raketsommar: Science fiction i Sverige 1950-1968” (“Rocket Summer: Science fiction in Sweden 1950-1968”) by Jerry Määtä.

August Blanche

|

A few hundred years after Mahabharata, there was in Athens a man called Theophrastus. Among many other things, he wrote something called The Characters. There he described different individuals: the flatterer, the chatterer, the boaster, the slanderer, the authoritarian, etc.

His friend and/or pupil Menandros (Menander) — or whatever their relationship was — wrote comedies using similar charcters. In his play Dyskolos (‘The Bad-Tempered Man’), the main character is a farmer, who is a real sourpuss.

The Roman playwrights Plautus and Terence adapted the stories by Menandros. Later, Shakespeare picked up the baton, and in the same tradition Molière wrote comedies like The Misanthrope, The Miser, The Imaginary Invalid, etc.

Inspired by a French writer, August Blanche wrote the aforementioned comedy in 1846 and based it on the same principles. “1846 and 1946” takes place in Stockholm, the Swedish capital, where it also had its opening night in 1846. The name of the main character is Bautastenius (roughly ‘Memorialstonius’). He is not an imaginary invalid, but he imagines he is a great archeologist.

He has a daughter, and she has a boyfriend, whom Bautastenius does not approve of. In that he is very similar to his forerunner, the farmer in Menandros’ Dyskolos, who puts to flight every dude from Athens who comes prowling around his daughter. Bautastenius wants to force his daughter to marry the King’s Chaplain, to whom he has willed away his fortune.

Bautastenius has a housekeeper, who is in charge of the housekeeping money. Furthermore he has workers digging in his garden. If his workers find a stone with a blunted bulge, Bautastenius considers it to be the head of a thousands of years old Greek statue with a lopped-off nose.

All of a sudden, the workers dig through the roof of an underground prison, where the Goddess of Truth has been jailed for thousands of years, for she has many enemies, she says.

Thankfully, she gives a mirror to Bautastenius. The mirror turns out to be a lie detector — or rather a truth detector. Bautastenius turns the mirror towards his housekeeper, who straightaway tells him that she every year steals 300 crowns of the housekeeping money, which makes it possible for her to support not only her family but all her relatives.

Terrified, Bautastenius turns the mirror towards his heir, the Royal Chaplain, who says that Bautastenius is a conceited idiot who thinks that he is a great archeologist.

Bautastenius says to the Goddess of Truth that he wants to be remembered after 100 years as a great archeologist. Will that happen? She sends him one hundred years ahead in time to 1946.

In 1946, I was thirteen years old, and a pupil at Vasa realskola in Stockholm, but I never met Bautastenius. He never turned up in that part of the city but rather outside the House of Nobility in the Old Town.

The House of Nobility is equipped with smokestacks. Bautastenius is told that the House has been changed into a steam-powered food manufacturing plant. Living cows and swine are thrown into the factory and they are turned into ready-cooked food.

”Who could imagine that the House of Nobility would become such a useful establishment?” Bautastenius exclaimed, thereby showing that August Blanche, who later became a liberal member of the Parliament, did not like the nobility.

In 1946, feminism was in full swing. Bautastenius meets a female lawyer, who tells him that her husband is a real gem, a good cook, good at cleaning, washing, and darning socks. And young boys are warned not to get together with girls. That could end in a disaster. In other words: life in the future is turned upside down.

While standing outside the House of Nobility a Västgötakalle — a strolling salesman from the province of Västergötland — comes flying along, pursued by a Chinese, who has been cheated by the salesman. They are both equipped with wings.

Then Bautastenius meets a young man whose name is Bautastenius. He doesn’t like his namesake, who says that his paternal grandfather was an archeologist.

“But then you must be my grandson,” Bautastenius exclaims. “But that is impossible. I have only a daughter.”

Bautastenius is now told that he had remarried later in life and had a son.

“Then you are my grandson,” he says.

“Well, well,” says the younger Bautastenius, “my paternal grandfather ended up in the madhouse of Danviken, because he thought he was a great archeologist. He believed it to such a degree that he was mummified and now that conceited Bautastenius is exhibited together with a stuffed dromedary at the entrance of the Royal Academy of Sciences.”

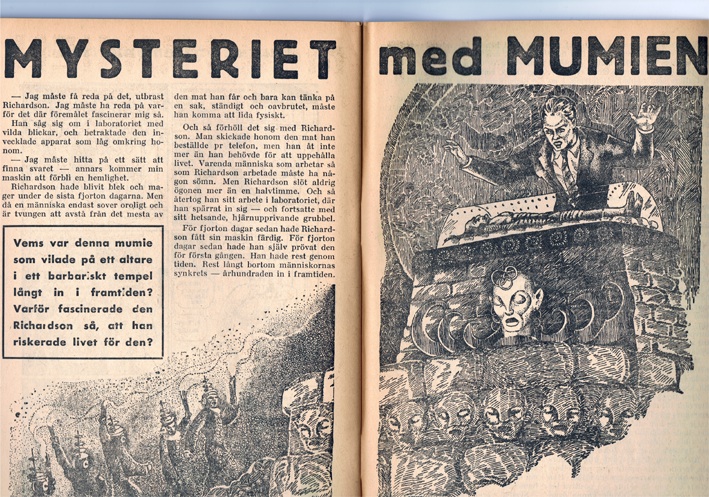

And here we have the first known time paradox in Swedish science fiction. Bautastenius exists in 1946 in the shape of a living time traveller at the same time that he is a mummy at the Royal Academy of Sciences. It is almost like a presage of the short story “The Mystery of the Mummy” by Duncan H. Farnsworth, published in Amazing Stories (vol. 15, number 9, September 1941), which actually was translated into Swedish and published two months later in the science fiction magazine Jules Verne Magasinet.

August Blanche was 95 years ahead of Duncan H. Farnsworth with an idea similar to the one Philip K. Dick later used in his short story “The Skull” (If no. 4, September 1952).

Extremely unhappy, Bautastenius returns to 1846, disinherits the Royal Chaplain, sacks the housekeeper, and accepts his daughter’s boyfriend. And he decides to change the future. This is what he says to his daughter:

Yes, I will bid defiance to the future. I will not remarry, you shall see to it; no more housekeepers in the house; no governesses — you hear that? And no maids either — send away every maid — otherwise I don’t know what I will do.

(To the boyfriend.) Sir! Is there a dromedary at the Academy of Science? Please, don’t sell me to the Academy — bury me well! I don’t want to be handed down as a stuffed nuisance to posterity!

Such thorough interferences cause more time paradoxes. The grandson he met in 1946 will never exist. His daughter thinks he has become raving mad, while in fact he has become in full possession of his faculties. Everything that is satire and comedy in Blanche’s play became common themes in the time-travel stories published in American pulp magazines in the 20th century.

On April 24, 1860 — fourteen years after August Blanche — the Swedish-Finnish newspaper Helsingfors Tidningar published the first instalment of the serial story Simeon Lewi resa till Finland år 5,870 efter werldens skapelse, efter de kristnes tideräkning det 1,900:de (“Simeon Lewi travels to Finland in 5,870 after the creation of the world; according to the Christian calendar, the year 1900”).

The events are supposed to take place in the year 1900, forty years ahead in time, forty years after being published in Helsingfors Tidningar. Every chapter consists of a letter Simeon Lewi wrote to his rabbi in London.

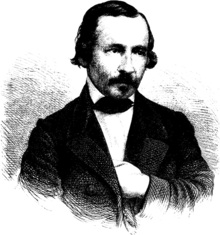

Zacharias Topelius

|

When the story about the Jewish traveller was published, the author was unknown, but the anonymous writer proceeded in a cheerful mood. In a foreword he tells that a telegraph of the future has been invented in America. It reports events before they happen:

With some insight into these known advances, one should not find it very surprising that the telegraph nowadays has become so rapid that it tells us about events that happen forty years from now. It could rather be supposed that this soon will be considered too slow; whereupon, beyond all doubt, one will bring news to such a perfection that it is received hundreds, nay, thousands of years before it happens; and when that is considered to be insufficient, the telegraph will ultimately, according to the normal cycling motion of things, reach the same height of perfection that oral rumour (often also the newspapers) has reached in our days; that is, they proclaim events that neither have happened nor will ever happen in this world.

We now get to know that the future telegraph has been prohibited because it disclosed stock exchange prices and similar news in advance.

Anyhow, now Simeon Lewi is in Finland and faithfully reports every day to his rabbi in London.

Thus, in 1860 Helsingfors Tidningar publishes these letters about events taking place in 1900. Now it so happens that Simeon Lewi arrives at the oldest city in Finland, Åbo, on June 9, 1900 and visits the library. There he finds the files of Helsingfors Tidningar from 1860.

You can understand what happens! To his surprise, Simeon Lewi can read not only all the letters he has written up to the day he visits Åbo, he can also read the letter he will write later that evening at his hotel room as well as the other letters he has not yet written to his rabbi.

Before the future telegraph was prohibited, someone had sent Simeon Lewi’s letters to Helsingfors Tidningar. We don’t know when, but it must have happened between 1860 and 1900, a period when the future telegraph had been invented but not yet prohibited. Undoubtedly, we here face time paradoxes.

Altogether, Helsingfors Tidningar published seventeen letters, and the last letter ended like this:

On top of the mountain you can see the observatory where, for the first time in Europe, they are said to have estimated the position of the central sun, in the way the Copernican system received its definitive perfection. In later days, it is also said that because of this discovery, it was here that they first of all succeeded in determining the movements of the solar system and laid the foundation of the theories that now constitute the highest triumphs of astronomy. (To be continued)

But there was no continuation. It seems that the future telegraph had been prohibited before all the letters could be published. Today we know that the author was no less than Zacharias Topelius, who with that at long last joins the tribe of science fiction writers.

Even in another old Swedish-language story, Claës Lundin’s Oxygen och Aromasia (1878; serialised in English by Bewildering Stories beginning in issue 256), news is published before it happens and is reported in newspapers like Next Week’s News and News of Tomorrow.

Ulf R. Johansson has asked me to mention a writer who has no connection to time paradoxes, but who at least wrote a future story. It takes place in Malmö, which gives it a regional Skåne connection. The author is none other than Axel Danielsson, who died prematurely in 1899 at the age of 36.

He founded the newspaper Arbetet (“The Worker”) in Malmö. He wrote the Social Democratic party manifesto of 1897 and as early as 1892 wrote the short story “Främlingen Ett besök i det nya samhället” (‘The Stranger: a Visit to the New Society’). It is about a man who returns to Malmö after 40 years and finds the Social Democratic society implemented. Women are placed on a level with men. Money does not exist. People use cards as we do today with Diners Club, MasterCard, Visa and American Express.

With the answer book in our hands, we can see that this is a political utopia that has become reality. Thank you for listening to me.

Copyright © 2010 by Bertil Falk